Justice comes at last:

Justice comes at last:

Tulia, Texas:

Small Town, Big Injustice

For a history of the case, click here

Recent developments in the case:

Texas Governor issues pardons for Tulia defendants; dirty cop indicted.

8/23/03, Los Angeles Times

35 Pardoned in Texas Drug Case

Final chapter closes on a misguided 1999 sweep. The informant whose word led to lengthy sentences for many is charged with perjury.

By Scott Gold, Times Staff Writer

HOUSTON - Marking the end of a criminal case that devastated a North Texas town, Gov. Rick Perry on Friday pardoned 35 people ensnared in a 1999 drug sweep, months after a state judge determined that the charges were founded on little more than innuendo.

The 35 residents of Tulia, Texas, almost all of them African American, were among 46 people who were arrested during the predawn raid, by far the biggest ever seen in the town of 5,000.

The charges, which brought many defendants lengthy prison sentences, were based on the allegations of a single informant, a man once celebrated in Tulia and given a Texas Lawman of the Year award. The informant, who worked alone and had virtually no evidence beyond his word - such as audiotapes of his supposed drug buys - has since been charged with perjury.

Most of the accused were released on bail in June after a state district judge determined that the informant, Tom Coleman, was "simply not a credible witness" and had withheld evidence. The judge also asked the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals to overturn the convictions; the appeals court has not yet weighed the case.

Prosecutors, who could not be reached Friday evening, have said they have no plans to file new charges against the defendants.

For the rest of this article, please go to The Los Angeles Times website.

7/24/03 Court reverses conviction of Tulia drug-sting victim

By GREG CUNNINGHAM, Amarillo Globe News

Nearly four years to the day after 46 people were arrested in the controversial 1999 Tulia drug sting, an Amarillo appeals court reversed the convictions of one of the defendants, a move that apparently will result in the first exoneration of a person convicted in the sting.

The 7th Court of Appeals, in an unpublished decision handed down Monday, reversed eight narcotics convictions against William Cash Love, who was handed sentences totaling 341 years by a Swisher County jury. The decision remanded Love's cases to district court for new trials

4/1/03 Judge recommends overturning Tulia cases

AUSTIN, TX -- Texas prosecutors on April 1, 2003 agreed to throw out the convictions of 38 people, nearly all of them black, who faced drug charges based on the uncorroborated testimony of a white former undercover police officer. The 1999 arrests stemmed from the work of a single undercover agent whom other law-enforcement officials said had faced theft charges and used a racial epithet. Defense attorneys claimed the prosecutions were racially motivated. The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals had ordered a hearing to review evidence against four of the defendants. The star witness during the hearing, which began last month and is scheduled to resume today, was undercover agent Thomas Coleman. Retired state district Judge Ron Chapman of Dallas recommended the appeals court grant new trials to everyone convicted as a result of the busts. For more information, do a search at www.amarillonet.com, website of the Amarillo Globe-News.

For a more detailed report from the Washington Post, click here.

Tulia, Texas: Small Town, Big Injustice

Beginning in the early morning hours of July 23, 1999, a small town of 5,000 in the Texas panhandle was transformed. Tulia went from being just another rural town in Swisher County with a great interest in school sports to ground zero in the US Drug War. Following an 18-month investigation by a white, undercover narcotics officer, Tom Coleman, the police began to round up and arrest 46 people, 39 of whom were African-American. The remaining had ties to the town's small, black community.

In the end, more than 10% of Tulia's black population were arrested. Almost all were charged with selling small amounts of powder cocaine, worth less than $200, to Coleman. The first defendants went to trial to prove their innocence, and were handed sentences of 60 and 90 years. First-time offenders with no prior convictions were being locked away for 20 years or longer. The others soon learned that the mostly all white juries were convicting people based solely on Coleman's word and one bag of powder cocaine, with no corroborating evidence. There were no audiotapes, no video surveillance, and no wiretaps to back up his testimony. No drugs, no money, and no guns were found in the sweep of these mostly poor people, living in public housing, modest homes and trailers. On the advice of their attorneys the remaining defendants began to plea bargain rather than to risk trial, as they felt the criminal justice system was stacked against them.

A few did admit that they sold crack to Coleman, but many believe that they were framed. In one small town, how could there be so many drug dealers? If everyone is dealing, who is buying? Where was the money? It just didn't add up. While some admit that they have seen marijuana and crack in town, none have seen the powder cocaine that Coleman claims to have bought. Where is the evidence?

All in all, 22 went to prison, many pled to get probation. A few had their charges dismissed. Billy Wafer was able to prove with his timecard and testimony of his boss that he was at work, not with Coleman at times the officer claimed. His charges were dropped, and he is suing for false arrest. Coleman also misidentified defendant Yul Bryant, who didn't match Coleman's description. His charges were dismissed. This has raised serious questions about Coleman's credibility.

Key information about Coleman's past was withheld at all the trials except one. For the most part, the juries were not able to hear about the charges against Coleman for his previous law enforcement job: abuse of official capacity, debts left behind, and theft by unauthorized use of a county credit card. A few law enforce-ment officers praise his work, but others criticize his tactics and call him a "compulsive liar". Coleman was named officer of the year in the Panhandle after the busts. He has since been fired from his next job for inappropriate behavior.

Though many in the town were happy to see the people that the local media labeled "known drug dealers" and "scumbags" being sent away, others in the community began to question the sting. How can so many lives be destroyed based solely on the word of a single, dubious officer? What role did racism play in the convictions of such a large part of the black community? Was there a policy in place of target-ing African-Americans to remove them from the area? Lawsuits have been filed by the NAACP and the ACLU against Coleman and Sheriff Larry Stewart of Swisher County for civil rights violations. The FBI is also looking into the situation. zealotry

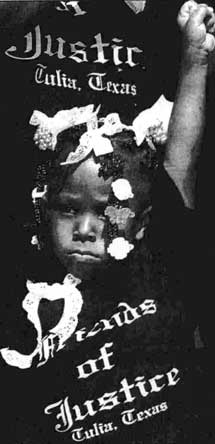

To support defendants and their families and bring attention to the situation, members of the Tulia community have come together to form the Friends of Justice. Their efforts have resulted in bills being introduced into the Texas State Legislature, called the Tulia Proposals, to prevent future such incidents.

Meanwhile, many families are waiting for their loved ones to come home from prison. The children orphaned by the drug sting have moved in with friends and relatives, adding more bodies to their over-crowded living situations. For some, racial tensions have increased, while others are coming together for the sake of the community. This travesty begs the broader question: Is Tulia really all that different other communities across America in the grips of Drug War hysteria?

In 2001 community organizers and family members went on a "freedom ride" for justice in the belief that these prisoners were victims of a gross miscarriage of justice.

Texas to Toss Drug Convictions Against 38 People

Prosecutor Concedes 'Travesty of Justice'

By Lee Hockstader

Staff Writer, Washington Post, April 2, 2003; Page A03

AUSTIN, April 1 -- Texas prosecutors today agreed to throw out the convictions of 38 people, nearly all of them black, who faced drug charges based on the uncorroborated testimony of a white former undercover police officer.

In a stunning reversal, the state agreed with defense lawyers that the former officer, Thomas Coleman, was an unreliable witness even though his testimony was the only evidence used to convict the defendants, some of whom are serving sentences of 90 years or more.

Asked if the convictions represented a travesty of justice, the state's special prosecutor, Rod Hobson, hesitated a moment and then said, "Yes."

It was a dramatic turn of events in a racially charged case that erupted into the national spotlight when more than a tenth of the black population of Tulia, a poor farming town in the Texas Panhandle, was arrested on cocaine charges in a 1999 sweep.

Of the 46 people originally arrested, 22 received prison sentences and 13 of them are still incarcerated, all on the say-so of Coleman, a police officer with a checkered past who offered no fingerprints, audio or video surveillance, corroborating witnesses or other evidence to support his testimony. A number of experienced Texas lawyers said they had never before seen convictions in a major drug case rest on the uncorroborated testimony of one police officer.

Civil rights groups cried foul. Both the U.S. Justice Department and the Texas Attorney General's office launched investigations into the Tulia bust. But even as evidence emerged as to Coleman's unreliable testimony and questionable character, the investigations seemed to go nowhere, and the convicts languished in prison.

Judge Ron Chapman, a retired jurist from Dallas who was appointed to preside over a hearing on the case, accepted the two sides' stipulation today that Coleman "is simply not a credible witness under oath." Nonetheless, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals has the final decision on the defendants, 27 of whom pleaded guilty after juries began handing out lengthy sentences to the defendants who first went on trial.

In a hearing in Tulia two weeks ago, Coleman took the stand and acknowledged there was no evidence beyond his testimony to support the convictions. He also acknowledged using a racial epithet to refer to blacks in conversations with his superiors.

When one of the defense lawyers asked him if he was sure all the defendants behind bars deserved to be there, Coleman replied, "I'm pretty sure." He also admitted to several "mess-ups" -- including false police reports -- that resulted in four other cases being dismissed.

The hearing turned into what seemed to many in the courtroom a trial of Coleman himself. He had run up a string of debts after quitting earlier jobs in law enforcement. He conceded that he once owned an illegal machine gun, and he was described by previous employers as dishonest, unreliable, a racist and, in one case, "a gun nut."

In a separate, civil rights case brought by one defendant, Coleman was asked in a deposition if he could affirm his earlier testimony at trial. He responded that some of his sworn testimony was "questionable."

Coleman, 43, could not be reached for comment today.

Technically, the hearing in Tulia last month was to collect evidence for a challenge filed by four defendants serving prison terms of 20 to 90 years. They sought to have their convictions overturned based on fresh evidence about Coleman's past.

"You can't rely on anything he says, even at the risk of letting a guilty person go," conceded the prosecutor, Hobson. "His testimony caused us confidence problems that undermined the integrity of the verdicts, and if you want to call that a travesty of justice, you can."

As a result, Hobson said the state would seek to vacate the convictions of all 38 defendants once prosecutors and defense lawyers formulate detailed "findings of fact" for Chapman to submit to the Court of Criminal Appeals. He said in the event new trials are granted by the court, the state would not again seek to prosecute any of the defendants.

Coleman was hired as an undercover officer by the Swisher County sheriff's office in 1998, and soon after that launched his 18-month investigation. It came into public view on July 23, 1999, when Coleman, wearing a ski mask, supervised the nighttime arrests of 46 people, 39 of them black, who he said had sold him drugs. Television cameras recorded many of the arrests.

For his work on the drug bust, he was named Texas's Lawman of the Year in 1999.

In the early trials, which resulted in swift convictions, no evidence was introduced about Coleman's record in law enforcement. Despite the fact that Coleman kept spotty records of his drug buys and that no drugs, weapons or large sums of cash were found to back up his testimony, tough sentences were imposed.

That, say defense lawyers, induced other defendants to plead guilty to a variety of charges.

It was an extraordinary turn of events in Tulia, a town of 5,000 midway between Amarillo and Lubbock. Blacks in the town, who number fewer than 400, were stunned by the drug bust, and many were adamant from the beginning that Coleman framed the defendants.

Dozens of Tulia's black residents attended the hearings earlier this month and heard testimony that confirmed their suspicion that Coleman was a racist.

"Not only did he use the n-word and other racial slurs to talk about black folks, but he did it in front of his superiors in the course of this investigation," said Mitchell E. Zamoff, a lawyer with Washington's Hogan & Hartson, which along with Wilmer Cutler & Pickering, another D.C. law firm, is handling a portion of the defense case pro bono.

Lawyers close to the case said that as part of today's agreement, Swisher County Commissioners Court would pay the defense $250,000, to be split among the defendants according to the amount of time spent incarcerated. In return, the defense would agree not to sue Swisher County, its sheriff or district attorney for civil rights damages.

© 2003 The Washington Post Company

POW Gallery